Wendy Arons, professor of dramatic literature at Carnegie Mellon University, sat down with Anya Martin to talk about the upcoming JH: Mechanics of a Legend.

Wendy: What originally drew you to become a director/writer of theater?

Anya: It’s twofold. The first is a kind of sentimental story but it’s true. The specific moment that I had, the “aha” moment was in the summer going into first or second grade, and I was at Mennonite Church Camp, Cove Valley Camp – and every year there’s a cabin talent show, there’s this competition of all the cabins all week long – the best soccer team, the team that cleans up their cabin best, the one that memorizes the most Bible verses – and our cabin was sadly lagging behind in everything. And I was, like, “we gotta do something here!” So I decided: we’re gonna take the talent show!

So I wrote this play about one of our devotional verses: “He who is in you, is greater than he who is in the world.” In it I was a little girl jumping on a bare mattress, and Satan came with his little demon, and it was like a comedy. Satan wore a cape, and he had this little demon who went “Yeah, yeah, uh-huh” after everything he said, and there was even this Vanna White character who broke the fourth wall and would tell the audience when to applaud, like when the little girl won. I chanted that verse til Satan ran away yelling “Aaaaahhh” as if he was melting. Needless to say, we won, and everyone talked about it all week, and I thought: this is what I’m supposed to be doing, this is how I am brave, this is how I chase off evil in the world.

Another important influence was and is my Aunt Marianne, my father’s sister. She is one of nine children and she went off to college and studied theater at a time when not a lot of people in her community did that. She was a huge inspiration to me, saw that I had talent and was really supportive of me. I knew that she was a director, and while most kids who have the theater bug end up wanting to act I knew very early that I also wanted to direct. I had one of those aspirational poems in middle school, the kind that say “Be what you want to be!” and I wrote DIRECTOR over top of it, and it was hanging in my bedroom for a really long time.

Wendy: What was the inspiration or impetus behind JH: MECHANICS OF A LEGEND?

Anya: There’s a long trajectory for that as well. I can remember being in elementary school and singing John Henry in fourth grade music class, and I found the irony of the song quite striking. I mean, the music’s playing and my class is singing so happily “he died with hammer in his hand, Lord, Lord, he died with his hammer in his hand.” And I’m thinking: this is really a sad song. It stuck with me.

So then when I started Hiawatha Project, that legend had always stayed with me, and one of Hiawatha’s missions is to use myth and legend. So, I thought: I really want to do a show about John Henry. For a hundred and fifty years artists of all kinds – musicians, painters, writers – have all been inspired by the story of John Henry, and I guess I am one of them. John Henry’s legend is in many ways a man versus machine story.

At first I thought the show was going to be about technology. I started by asking myself “What machines are we racing against now? What hammers will we die holding?” Thinking the show would be something about iphones, screens, and disconnection. And then in my research I came across Scott Reynolds Nelson’s book Steel Drivin’ Man, and the conversation took a dramatic shift. Nelson’s book is about the “real” John Henry – a black man who lived through the Civil War, only to be unjustly imprisoned and leased out to a railroad work camp in the 1870’s. As a result of the horrific work conditions there, he tragically dies working – or perhaps racing — along side a steam drill. But the steam drill wasn’t the machine that killed him – rather the machines that killed him were complex and insidious societal machines at work during Southern Reconstruction – machines devised to maintain a mechanical advantage to a certain class of white men — machines such as racism, industrialization, and capitalism built on the backs of an oppressed people.

This realization began a whole other turn of research into the economics of slavery and into the historical context of the Reconstruction era, and to many conversations about machines, to the science of mechanics, and definitions of mechanical properties, and to ideas of how to use these in poetic ways to create metaphors for societal machines.

Wendy: What has been the most challenging thing about the process for this show?

Anya: The most difficult thing about the show has been the research. Not the magnitude of the research – although there has been a lot – but the continued reveals within the research pertaining to the horrors of slavery and the human condition and in understanding the historical context of America’s wealth and power as a result of slavery. Just when you think you know how horrible human beings can be to one another, there seems to be a new realization of that on different levels in the research – of the reach of the atrocities during slavery and into Reconstruction. And then, as an artist, internalizing that and empathizing with those stories has been really difficult. Really important, but very, very difficult. Particularly, the research into slave babies and children and the abuse and systematic torture they endured. It’s so difficult to read it on the page, and then continually internalize it through the work. I’d say that’s the hardest part of this particular show.

Wendy: What has been the scariest thing about this work?

Anya: The scariest thing is how topical the work has become. That is also why I’m doing it, and why I think it’s really important, but in some ways that is also the scariest part of it. I chose the piece because I believed the social issues were relevant, but throughout the last couple of years tragedies like the one that occurred in Ferguson have brought a new urgency and relevancy to the work. As the ballad of John Henry says, “A man ain’t nothing but a man” and to be just one person, an artist, trying to interpret such an important and large story is a lot of responsibility which can feel overwhelming, even frightening at times. However, I think “A man ain’t nothing but a man” also means that we are all equals on some level, you work with what you have as a person and as an artist and you give what you have to give – you interpret and offer up your perspective as a part of this greater conversation. So this is also what is inspiring about this work.

Wendy: What has been the most exhilarating thing so far?

Anya: I’m just really proud of the work. The work came from really big ideas. From this notion that we could use ideas of machines and mechanics in a poetic way to talk about man-made machines, and take this ballad and the legend and combine it all and make it work. What has been the most gratifying is that all these really big ideas and metaphors that I’ve been formulating in my head and grappling with over the past 2 years – they do work, and that the piece has evolved as a kind of long form poem.

To take many ideas that appear dissimilar and find out that they hold similar truths within them has been really satisfying. It’s in Hiawatha’s artistic statement to find the universal and infinite in the ordinary and specific. Thornton Wilder said he believed he found the universe in the most mundane things. To take these two abstract ideas that stand for various metaphors in my head and to put them all together and they end up commenting on each other and having a conversation and revealing larger truths in a poetic way that I could never have imagined has been really satisfying.

That and getting to work with an amazing group of people on this show has been really exhilarating and wonderful. Everyone has been truly invested, and has brought their personal reflections as well as their own research, heart, and ideas. The conversations we’ve had creatively and about the issues have been really grounding and purposeful.

Wendy: What do you hope an audience member will take from JH: Mechanics of a Legend?

Anya: I hope they have a really entertaining evening, and that they are surprised and engaged and pulled into the story and to the issues being explored in a way that was completely unexpected for them. I also hope that they will look at the piece and begin to recognize the societal machines that they are currently in and their place in them, whether they’ve chosen to be there or not, and contemplate how we can build a better societal machine, going forward.

Wendy: What will be the next steps after this workshop?

Anya: We’re going to take the feedback from the talkback and reflect and mull on it and sit with it for a time. Then the goal is to revise the script and have a staged reading sometime in the next six months. And then to fully produce the work for a month long run. We’d love to partner with a producing organization here in Pittsburgh to fully produce the work. Or Hiawatha will fully produce it. But the goal is to revise, reflect, engage with the communities that are interested in the story, and then fully produce the work within the next year to year and half, depending on how funding cycles pan out.

Wendy: What are some of your favorite theatrical conventions?

Anya: I love breaking the fourth wall. I love clean and concise blocking that reveals something not necessarily in the writing, that’s telling a parallel story. I love playing unexpectedly with the subtext of a line. And I also love throwing a good love story into every show.

Wendy: What makes Hiawatha Project unique within the Pittsburgh theatre community?

Anya: Hiawatha Project is the only company that produces only original work through a long term creation cycle. I believe we’re the only company dedicated to only devised work. I also think we’re the only company dedicated to only devised work about specific social issues. Some companies in town occasionally do a devised piece, but the level of investment and intention that Hiawatha Project employs in developing its works is truly unique in Pittsburgh.

Wendy: Tell me more about the process you engaged in for devising this work.

Anya: Hiawatha has what I call a seven-phase creation cycle, which generally takes place over the course of two years. The first two phases are about identifying a social question or story and then researching all aspects of that initial impulse – allowing the research and ideas to lead me as an artist down unexpected roads – to let the work direct me so to speak – before I start directing it.

In phase three I begin to develop the work with artistic and community partners. For this work I immediately reached out to Monteze and shortly thereafter to Britton and Kyle. Monteze and I had conversations about the oral history of John Henry and its significance in his own memory and community as a child, as well as many conversations about Nelson’s book. Britton and I probably had hundreds of discussions about mechanics and the six classic simple machines, and the societal metaphors within those mechanizations. Kyle helped to break down the dramatic structure of the legend and of Nelson’s book as well as aided me in an immense amount of research – digging through primary source material for references to machines and hammers and the like.

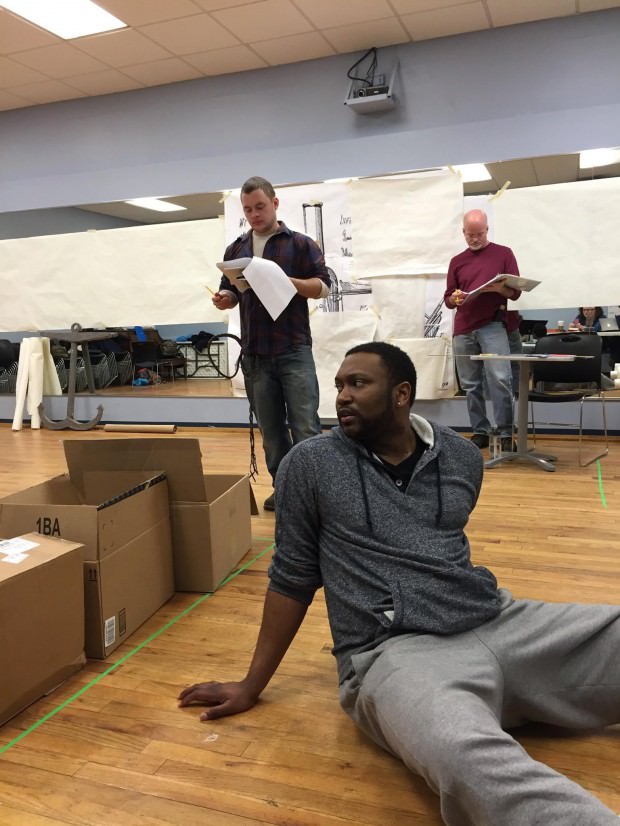

Since September all of the designers and performers have participated in monthly workshops exploring the major ideas for the show. At these workshops we discussed everything from our personal experiences with racism to some of the most shocking slave narratives, to news articles connecting our discoveries to current issues. We tried to be honest with our investigations and ourselves. We made ourselves vulnerable to the work and to each other. We created machines out of 150 year old tools from Carrie Furnace, on loan from the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area, as well as made machines out of our own bodies, and machines out of sounds and song. Now we are in phase four of the creation cycle, when I mold all of the material we have been developing into a more formal script and direct the show for a work-in-progress presentation. This presentation is meant to gather feedback and responses to the work – as a means of further developing and deepening the artistic work – and as a means to further connect to communities interested in the social issues explored in the work.

In phases 5 and 6 – I reflect on the feedback from the work-in-progress and further revise the script. In phase 7 the work will be fully produced in Pittsburgh.